“People will not look forward to posterity who never look backward to their ancestors.”

– Edmund Burke

St Patrick; From Slave to Saint.. This historical journey begins ‘lightly’, with the Shamrock, and is Dedicated to my Father, having passed away early last year and was originally from Ireland.

One traditional symbol of Saint Patrick’s Day is the Shamrock. (See more symbols at the end of this article..)

“Shamrock” is the common name for several different kinds of three-leafed clovers native to Ireland.

The shamrock was chosen Ireland’s national emblem because of the legend that St. Patrick had used it to illustrate the doctrine of the Trinity. The Trinity is the idea that God is really three-in-one: The Father, The Son and The Holy Spirit.

Patrick demonstrated the meaning of the Three-in-One by picking a shamrock from the grass growing at his feet and showing it to his listeners. He told them that just as the shamrock is one leaf with three parts, God is one entity with three Persons.

The Irish have considered shamrocks as good-luck symbols since earliest times, and today people of many other nationalities also believe they bring good luck.

Legend (dating to 1726, according to the (Oxford English Dictionary) credits St. Patrick with teaching the Irish about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity by showing people the shamrock, a three-leafed plant, using it to illustrate the Christian teaching of three persons in one God.[65] For this reason, shamrocks are a central symbol for St Patrick’s Day.

The shamrock had been seen as sacred in the pre-Christian days in Ireland. Due to its green color and overall shape, many viewed it as representing rebirth and eternal life. Three was a sacred number in the pagan religion and there were a number of “Triple Goddesses” in ancient Ireland, including Brigid, Ériu, and the Morrigan.

Excerpt from the Down Cathedral: Tradition has it that Saint Patrick brought the Faith to the country in the early part of the fifth century. Patrick was a North Briton who was captured by a party of raiding Irishmen and brought to Ireland as a slave. During his years of captivity, he spent much time in prayer and would say as many as one hundred in a day, as he tells us in his Confession.

However, after six years of slavery and hardship, he escaped and boarded a ship. We cannot say if the ship was bound for Britain or Gaul, but we do know that he was re-united with his family. Patrick then tells of a dream in which a man named Victoricus brings him a letter. It was headed ‘The Cry of the Irish.’ While reading it, in his imagination he heard voices calling: ‘Holy Boy, we are asking you to come and walk among us again’. Thus far, we have Patrick’s own story, told in his Confession. Patrick’s two principal biographers, Muirch and Tirechan, both writing some centuries later, take up the story.

We are told that Patrick landed first on the coast of Wicklow and from there travelled northwards as far as Strangford Lough where he landed at the mouth of the River Slaney near Saul. Here he met the local chieftain, Dichu, whom he converted to Christianity and who gave him a barn as his first church. The present Church of Ireland church at Saul, 2 miles distant from Down Cathedral, was built in 1932 to commemorate the fifteen hundredth anniversary of Patrick’s arrival. Patrick spent many years travelling among the Irish, converting the people to Christianity, consecrating bishops and founding churches as he went. (Scroll to the bottom of page for an image of Down Cathedral)

The version of the details of his life generally accepted by modern scholars, as elaborated by later sources, popular writers and folk piety, typically includes extra details such that Patrick, originally named Maewyn Succat, was born in 387 AD in (among other candidate locations, see above) Banna venta Berniae to the parents Calpernius and Conchessa.  At the age of 16 in 403 AD Saint Patrick was captured and enslaved by the Irish and was sent to Ireland to serve as a slave herding and tending sheep in Dalriada. During his time in captivity Saint Patrick became fluent in the Irish language and culture. After six years Saint Patrick escaped captivity after hearing a voice urging him to travel to a distant port where a ship would be waiting to take him back to Britain. On his way back to Britain Saint Patrick was captured again and spent 60 days in captivity in Tours, France. During his short captivity within France, Saint Patrick learned about French monasticism. At the end of his second captivity Saint Patrick had a vision of Victoricus giving him the quest of bringing Christianity to Ireland. Following his second captivity Saint Patrick returned to Ireland and, using the knowledge of Irish language and culture that he gained during his first captivity, brought Christianity and monasticism to Ireland in the form of more than 300 churches and over 100,000 Irish baptised. (Read more at Wiki)

At the age of 16 in 403 AD Saint Patrick was captured and enslaved by the Irish and was sent to Ireland to serve as a slave herding and tending sheep in Dalriada. During his time in captivity Saint Patrick became fluent in the Irish language and culture. After six years Saint Patrick escaped captivity after hearing a voice urging him to travel to a distant port where a ship would be waiting to take him back to Britain. On his way back to Britain Saint Patrick was captured again and spent 60 days in captivity in Tours, France. During his short captivity within France, Saint Patrick learned about French monasticism. At the end of his second captivity Saint Patrick had a vision of Victoricus giving him the quest of bringing Christianity to Ireland. Following his second captivity Saint Patrick returned to Ireland and, using the knowledge of Irish language and culture that he gained during his first captivity, brought Christianity and monasticism to Ireland in the form of more than 300 churches and over 100,000 Irish baptised. (Read more at Wiki)

According to the Annals of the Four Masters, an early-modern compilation of earlier annals, his corpse soon became an object of conflict in the Battle for the Body of St. Patrick.

“I Patrick, The Sinner..” by Bridget Haggerty

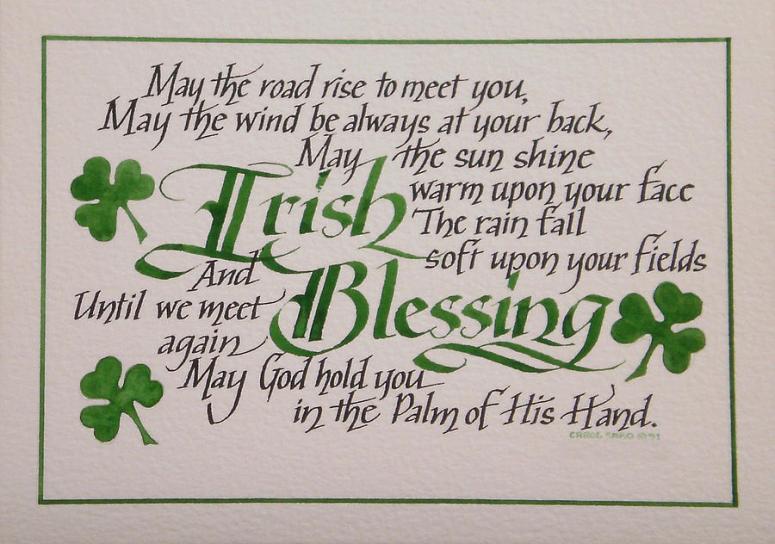

The high veneration in which the Irish hold St. Patrick is evidenced by the common salutation, “May God, Mary, and Patrick bless you.” His name occurs widely in prayers and blessings throughout Ireland and it is said that he promises prosperity to those who seek his intercession on his feast day, which marks the end of winter.

The high veneration in which the Irish hold St. Patrick is evidenced by the common salutation, “May God, Mary, and Patrick bless you.” His name occurs widely in prayers and blessings throughout Ireland and it is said that he promises prosperity to those who seek his intercession on his feast day, which marks the end of winter.

Crops could not be safely planted, nor animals put out in the fields, before the fear of winter frost had passed. The appearance in one’s garden of snowdrops, daffodils and crocus were fickle forecasters of better weather, as often as not popping up too soon, only to be covered by a late snow, or shriveled up by a sudden blast of frost. Indeed, such was the importance of getting the planting date correct, that the Celts had markers, to remind them when it was safe to plant, and later on, the early Christian Irish adopted these days as Saint’s days, for St Brigid (Feb 1) and St Patrick (March 17). Thus the proverb went: “Every second day is good, from my day forward” says Brigid. “Every day is good from my day forward” says Patrick.

All well and good. But who was this man who legend says drove the snakes out of Ireland and used a shamrock to convert the heathens?

The Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters state that by the year 438 Christianity had made such progress, the laws were changed to agree with the Gospel. In just 6 years, a 60 year old man was able to so change the country that even the laws were amended. He had no printing press, no finances, few helpers and Ireland had no Roman roads on which to travel.

Recorded history and mystical legend are cavalierly intertwined when it comes to St. Patrick. Some historians say he was born in Banwen, Wales. Others say it was Kilpatrick, near Dumbarton, in Scotland . As with many of the facts about his life, no-one is exactly sure where.

Even the date of his birth is disputed, although many historians place it about 385 A.D. Most of what is known comes from the saint’s Confessions, a slim volume which he wrote before he died in the late 400s.

In Patrick’s youth, the Roman Empire was in decline; without Roman protection, Britain was vulnerable to attack by marauding Irish pirates whose homeland had never been conquered or absorbed by Rome.

After one such raid, Patrick became one of the thousands captured and returned to Ireland as slaves; this was a devastating shock for one who had enjoyed a life of relative comfort as the son of a well-compensated church official.

Not only was he torn from home and family, but he also was taken to a land that, while not very distant, had to have seemed incredibly alien and frightening.

Roman expansion into Britain had brought law and order, advanced culture and infrastructure, and eventually, Christianity. Ireland, on the other hand, remained a harsh, difficult place where warring kings ruled violent small kingdoms and pagan priests performed human sacrifice.

Patrick was purchased by a Druid. Members of this mystical Celtic religion practiced magic, oversaw rituals and served as judges in the top echelons of ancient Irish society.

Once indifferent to the Christian teachings of his family, Patrick’s attitude changed radically during his six-year captivity. As a shepherd in his master’s lonely, misty fields, he writes of having only two constant companions – hunger and nakedness. In this isolated and degrading situation, Patrick wrote of his spiritual transformation: “The love of God – grew in me more and more, – in a single day, I have said as many as a hundred prayers, and in the night, nearly the same – I prayed in the woods and on the mountain, even before dawn. I felt no hurt from the snow or ice or rain.”

Patrick dreamed of escape. He tells us that he stole away one night and hiked 200 miles to the nearest port, where he found a ship that was soon to embark. But, because he was a penniless slave, the captain refused him passage. Patrick then prayed for several hours in a nearby wood; he returned to the ship, and miraculously the captain relented and gave him a place on the ship, possibly as a sailor.

History does not record precisely where the ship landed, but it was most likely along the coast of France, then known as Gaul. Details about how Patrick finally reached his family in Britain are also very sketchy. But, he did make it home and was haunted by his experiences in Ireland.

Convinced that God had summoned him to return to the pagan land of his captivity, Patrick trained for the priesthood. Some historians believe that he did so in France under the tutelage of St. Germain. Others say he trained in Rome. Regardless, he was assigned as a missionary to Ireland.

A few others had preceded him but with little success. Patrick’s immediate predecessor, in fact, was said to have been martyred. Territorial kings and intransigent Druids proved powerful barriers to Christianity, then synonymous with Roman domination as the church and its popes filled the void left by departing emperors.

Patrick faced very real danger but had an advantage. Having lived among the Irish for six years, he was familiar with their ways. That and a persuasive personality were vital to his eventual success.

Though Ireland is smaller than the state of Maine, it had many kings, each ruling tiny kingdoms called tuatha. Above them were kings of the five provinces, in turn subject to the high king seated at Tara, then the capital. Patrick knew he had to appeal to the fiercely independent minor monarchs in order to spread his message safely. Greasing their royal palms helped.

“I spent money for your sake in order that they might let me enter,” he addresses his superiors, recounting his mission in Confessions. “I made presents to the kings, not to mention the price I paid to their sons who escorted me.”

Underscoring the need for such royal protection, Patrick frequently referred to the dangers he faced in Ireland. Sometimes, the patronage of a king wasn’t enough to keep him safe.

At one point, he tells of being attacked, bound, robbed and threatened with death, all while under “protection.” But because the kings constantly battled with each other, it was important to court all of them.

Having friends in high places helped Patrick’s mission in other ways. Although he made few converts among kings who offered him safe passage, their fortunes being too closely related to maintaining the old order, his message often attracted other members of the royal families with less to lose, including younger brothers with little hope of inheritance from their fathers.

As Ludwig Bieler, the mid-century church historian, noted, when the highest echelon of society adopted the new faith, the people often followed.

But royal favor doesn’t begin to explain Patrick’s transforming effect on the people. History cannot always interpret such intangibles. There is little contemporary documentation of Patrick’s mission by chariot throughout Ireland, converting thousands and establishing churches.

Later hagiographers — people who write about saints — give vivid yet ultimately unreliable details about Patrick’s conversions and wondrous acts. His most famous “miracle,” driving the snakes out of Ireland, certainly is legend – geologists say the island broke off the European continent before snakes could evolve there. The story most likely is intended to be emblematic of how he purged paganism.

But Patrick’s dynamism was so great that myths abounded. “He must have been a terrifically charismatic figure,” says Robert Mahony, an associate professor of English at Catholic University and former director of the Center for Irish Studies there. “And such people inspire legends.”

One legend that is not widely known is Les Fleurs de St-Patrice which says that Patrick was sent to preach the Gospel in the area of Bréhémont-sur-Loire. He went fishing one day and had a tremendous catch. The local fishermen were upset and forced him to flee. He reached a shelter on the north bank where he slept under a blackthorn bush. When he awoke the bush was covered with flowers. It was Christmas day and from that time on, the bush flowered every Christmas until it was destroyed in World War I. The phenomenon was seen and verified by various observers, including official organizations. Today, St. Patrick is the patron of the fishermen on the Loire and, according to a modern French scholar, the patron of almost every other occupation in the area.

One legend that is not widely known is Les Fleurs de St-Patrice which says that Patrick was sent to preach the Gospel in the area of Bréhémont-sur-Loire. He went fishing one day and had a tremendous catch. The local fishermen were upset and forced him to flee. He reached a shelter on the north bank where he slept under a blackthorn bush. When he awoke the bush was covered with flowers. It was Christmas day and from that time on, the bush flowered every Christmas until it was destroyed in World War I. The phenomenon was seen and verified by various observers, including official organizations. Today, St. Patrick is the patron of the fishermen on the Loire and, according to a modern French scholar, the patron of almost every other occupation in the area.

Thomas Cahill, author of How the Irish Saved Civilization, believes that part of Patrick’s appeal lay in his message. In a 1996 CNN interview, Cahill noted that “the Christianity that Patrick planted in Ireland was really of a unique kind, in the sense that he left behind all of those dark, sad mediations on human sinfulness that were favorites of the fathers of the Church, and instead he concentrated on the goodness of creation.

“The Irish were already very mystical. They believed that the world was a magical place, and he built on that rather than on this human sinfulness theme, and, as a result, early Irish Christianity was extremely celebratory of the world, of the earth, of matter, of human experience, of the human body. It gets off the ground very quickly in this kind of dance of happiness and joy which is very unlike the sound of earlier Christianity.”

There is no reliable account of St. Patrick’s work in Ireland. Legends include how he described the mystery of the Trinity to Laoghaire, high king of Ireland, by referring to the shamrock, and that he singlehandedly–an impossible task–converted Ireland. Nevertheless, Saint Patrick established the Church throughout Ireland on lasting foundations: he travelled throughout the country preaching, teaching, building churches, opening schools and monasteries, converting chiefs and bards, and everywhere supporting his preaching with miracles.

His writings show what solid doctrine he must have taught his listeners. His “Confessio” (his autobiography, perhaps written as an apology against his detractors), the “Lorica” (or “Breastplate”), and the “Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus,” protesting British slave trading and the slaughter of a group of Irish Christians by Coroticus’s raiding Christian Welshmen, are the first surely identified literature of the British or Celtic Church.

What stands out in his writings is Patrick’s sense of being called by God to the work he had undertaken, and his determination and modesty in carrying it out: “I, Patrick, a sinner, am the most ignorant and of least account among the faithful, despised by many. . . . I owe it to God’s grace that so many people should through me be born again to him.”

St. Patrick died at Saul (Sabhall) on March 17 493. Saint Tassach administered the last rites and his remains were wrapped in a shroud woven by Saint Brigid. The bishops, clergy and the faithful from all over Ireland crowded around his remains to pay due honor to the Father of their Faith. Some of the ancient Lives record that for several days the light of heaven shone around his bier. His remains were interred at the chieftan’s fort two miles from Saul. Centuries later, the cathedral of Down was built where St. Patrick was buried.

There is another old legend that promises that on the last day, though Christ will judge all the other nations, it will be St. Patrick sitting in judgment on the Irish. In an interview, when Thomas Cahill was asked whether that spelled good news or bad news for the Irish, Cahill didn’t hesitate. “That’s great news for the Irish!” Resources: The Irish Heritage Newsletter and several web sites including The Catholic Messenger.

A Concise History of St Patrick via ‘Gaelic Matters.com‘ [<click for the full story]

While Patrick gets the credit for converting the Irish Celts to Christians, he wasn´t the first priest in Ireland. Believe it or not, when he arrived, there was probably already a substantial number of Christians in Ireland.

There is also not much evidence in St Patrick´s background to suggest that Patrick was a serious academic theologian. However, what makes St Patrick´s history unusual, is that he was one of the first to really try to convert non-Christians. While other clerics concentrated on working with the already established Christian community, Patrick had an evangelical zeal. As a bishop he made great efforts preaching the Christian word to the non-Christians Celts.

Rhodium Plated

Other St Patrick’s Day Symbols:

Leprechauns:

The name leprechaun comes from the old Irish word “luchorpan” which means “little body.”

A leprechaun is an Irish fairy who looks like a small, old man about 2 feet tall. He is often dressed like a shoemaker, with a crooked hat and a leather apron.

According to legend, leprechauns are aloof and unfriendly. They live alone, and pass the time making shoes. They also have a hidden pot of gold!

Treasure hunters can often track down a leprechaun by the sound of his shoemaker’s hammer. If the leprechaun is caught, he can be threatened with bodily violence to tell where his treasure is, but the leprechaun’s captors must keep their eyes on him every second. If the captor’s eyes leave the leprechaun – he’s known to trick them into looking away – he vanishes and all hopes of finding the treasure are lost.

The Color Green:

Believe it or not, the color of St. Patrick was not actually green, but blue! In the 19th century, however, green became used as a symbol for Ireland. In Ireland, there is plentiful rain and mist, so the ‘Emerald Isle’ really is green all year-round. The beautiful green landscape was probably the inspiration for the national color.

Wearing the color green is considered an act of paying tribute to Ireland. It is said that it also brings good luck, especially when worn on St. Patrick’s Day.

Many long years ago, playful Irish children began the tradition of pinching people who forgot to wear green on St. Patrick’s Day and the tradition is still practiced today.

The Harp:

The harp is an ancient musical instrument used in Ireland for centuries. It is also a symbol of Ireland. Harpists, who were often blind, occupied an honored place in Irish society. Harpists and bards (or poets) played an important role in the social structure of Ireland. They were supported by chieftans and kings.

Although it is not as recognizable as the shamrock, the harp is a widely used symbol. It appears on Irish coins, the presidential flag, state seals, uniforms, and official documents.

O’Carolan was one of the most famous harpists, and many Irish melodies inspired by him still survive to this day.

The Celtic Cross:

Saint Patrick was familiar with the Irish language and culture, because of his time as a slave there. When Patrick went back to Ireland to convert the Irish to Christianity, he was successful because he didn’t try to make the Irish forget their old beliefs. He combined their old beliefs with the new beliefs.

One example of this is the Celtic Cross. Saint Patrick added the sun, a powerful Irish symbol, onto the Christian cross to create what is now called a Celtic cross, so that the new symbol of Christianity would be more natural to the Irish.

The Blarney Stone:

The word “Blarney” has come to mean nonsense or smooth flattering talk in almost any language. Tradition says that if you pay a visit to Blarney Castle in County Cork and kiss the Blarney Stone, you’ll receive the gift of eloquence and powers of persuasion, a true master of the “gift of gab.”

The Blarney Stone is a stone set in the wall of the Blarney Castle tower in the Irish village of Blarney.

The castle was built in 1446 by Cormac Laidhiv McCarthy (Lord of Muskerry) — its walls are 18 feet thick (necessary to stop attacks by Cromwellians and William III’s troops). Thousands of tourists a year still visit the castle.

The origins of the Blarney Stone’s magical properties aren’t clear, but one legend says that an old woman cast a spell on the stone to reward a king who had saved her from drowning. Kissing the stone while under the spell gave the king the ability to speak sweetly and convincingly.

It’s difficult to reach the stone — it’s between the main castle wall and the parapet. Kissers have to lie on their back and bend backward (and downward), holding iron bars for support.

The world famous Blarney Stone is situated high up in the battlements of the castle. Follow one of the several long, stone spiral staircases up to the top and enjoy the spectacular views of the lush green Irish countryside, Blarney House and The Village of Blarney.

The stone is believed to be half of the Stone of Scone which originally belonged to Scotland. Scottish Kings were crowned over the stone, because it was believed to have special powers.

The stone was given to Cormac McCarthy by Robert the Bruce in 1314 in return for his support in the Battle of Bannockburn.